כחלק מה“נהדה” התרבותית, גם המוזיקה הערבית המסורתית עברה תחייה והתחדשות במהלך המאה ה-19 ובראשית המאה ה-20. מלחינים ומוזיקאים כמו עבדוה אל–חאמולי (عبده الحامولي, 1901-1836), סלאמה חגאזי (سلامة حجازي, 1917-1852), סיד דרוויש (سيد درويش, 1923-1892) ומוחמד עבד אל–ווהאב (محمد عبد الوهاب, 1991-1902), הביאו לשגשוגה של המוזיקה הערבית, שאבו השראה מסגנונות אחרים, המציאו מקאמים חדשים, והתאימו כלי נגינה מערביים ללחנים הערביים. במקרה של עבד אל–ווהאב, למשל, הוא הושפע מסגנונות מוזיקליים מערביים ולטיניים (טנגו, רומבה וכיו“ב), השתמש בכלי נגינה מערביים, וכן נהג להשתמש בתִווּי המערבי, שלא היה מקובל במוזיקה הערבית קודם לכן.

הקונגרס הבינלאומי הראשון למוזיקה ערבית שהתקיים בקהיר ב-1932 היה אפוא אחד מרגעי השיא של התחדשות זו, ואין פלא שאת האירוע ליוו גם מוזיקאים ומוזיקולוגים בעלי שם מהמערב, דוגמת המלחין והפסנתרן ההונגרי בלה בארטוק (Béla Bartók, 1945-1881), המלחין והמנצח הגרמני פאול הינדמית (Paul Hindemith, 1963-1895), המוזיקולוג והצייר הצרפתי רודולף ד‘ארלנגר (Rodolphe d’Erlanger, 1932-1872), המוזיקולוג הבריטי הנרי ג‘ורג‘ פארמר (Henry George Farmer, 1965-1882), המוזיקולוג היהודי–גרמני קורט זאקס (Curt Sachs, 1951-1881) והאתנו–מוזיקולוג הגרמני רוברט לכמן (Robert Lachmann, 1939-1892).

גם נוכחותם של היהודים הערבים בלטה במיוחד. כך, למשל, לבד מהזמר המוסלמי מוחמד אלקבנג‘י (محمد القبنجي), כל נגני המשלחת העיראקית היו יהודים. בעיראק, אולי יותר מבכל ארץ ערבית אחרת, התערו היהודים בתרבות הערבית והאסלאמית. אם בזכות קדמוניות הקהילה היהודית שם, אם מכיוון שבני ובנות הקהילה זכו לחינוך בערבית הספרותית גם אם למדו בבתי ספר זרים – יהודים לקחו חלק משמעותי בהתפתחותה של התרבות העיראקית. במחצית הראשונה של המאה ה-20, סופרים ומשוררים יהודים כמו מוראד מיכאל, יעקב בלבול, מאיר בצרי, ובמיוחד אנוור שאור, הותירו את חותמם על הספרות והשירה הערבית בכללה, והעיראקית בפרט. אחדים מהם – כמו סמיר נקאש וסמי מיכאל – אף המשיכו לכתוב ולפרסם בערבית גם לאחר שהיגרו לישראל במחצית השנייה של אותה מאה.

בתחום המוזיקה, העמידה יהדות עיראק שורה ארוכה של יוצרים שזכו להכרה רחבה ולתהילה, לא רק בקרב קהילתם כי אם בקרב כלל החברה בעיראק. למעשה, עד עצם היום הזה חלק נכבד מהשירים שנחשבים כשירים “עיראקיים עממיים” הולחנו על ידי האחים היהודים סאלח (1986-1908) ודאוד (1976-1910) אלכוויתי (דאוד אלכוויתי הוא סבו של הזמר הישראלי דודו טסה), שהיו גם נגני עוּד וכינור, בוצעו על ידי הזמרת היהודייה סלימה באשא מוראד (1974-1912), ונוגנו במקור על ידי נגנים יהודים. ייתכן שמכיוון שחלק גדול מכלי הנגינה, ובמיוחד כלי מיתר, היו אסורים מבחינה הלכתית לפי האסלאם, היו אלה בעיקר יהודים שלמדו לנגן בהם, ויהודים היו גם אלה שהרכיבו את רוב התזמורת הראשונה של רשות השידור העיראקית, שהוקמה ב-1936 על ידי האחים כוויתי. כיום, יש היודעים לספר כי עם עזיבתם של היהודים את עיראק בראשית שנות ה-50, המוזיקה העיראקית שבקה חיים והתפתחותה נעצרה למשך עשור.

לא ייפלא כאמור, שלבד מהזמר המוסלמי, המשלחת שנבחרה לייצג את עיראק באותו קונגרס בקהיר הורכבה כולה מנגנים יהודים: עזרא אהרון ניגן על עוּד, יוסף זערור על קאנון, יוסף פתו על סנטור, אברהם סאלח שמחה על רִיק (תוף מסגרת), סאלח שמואל על ג‘וּזַה (כלי מיתר) ויהודה מוסא שמש על תוף גביע. עזרא אהרון, שנבחר לעמוד בראש המשלחת והופיע תחת השם “עזורי אפנדי“, נבחר למוזיקאי הטוב בקונגרס.

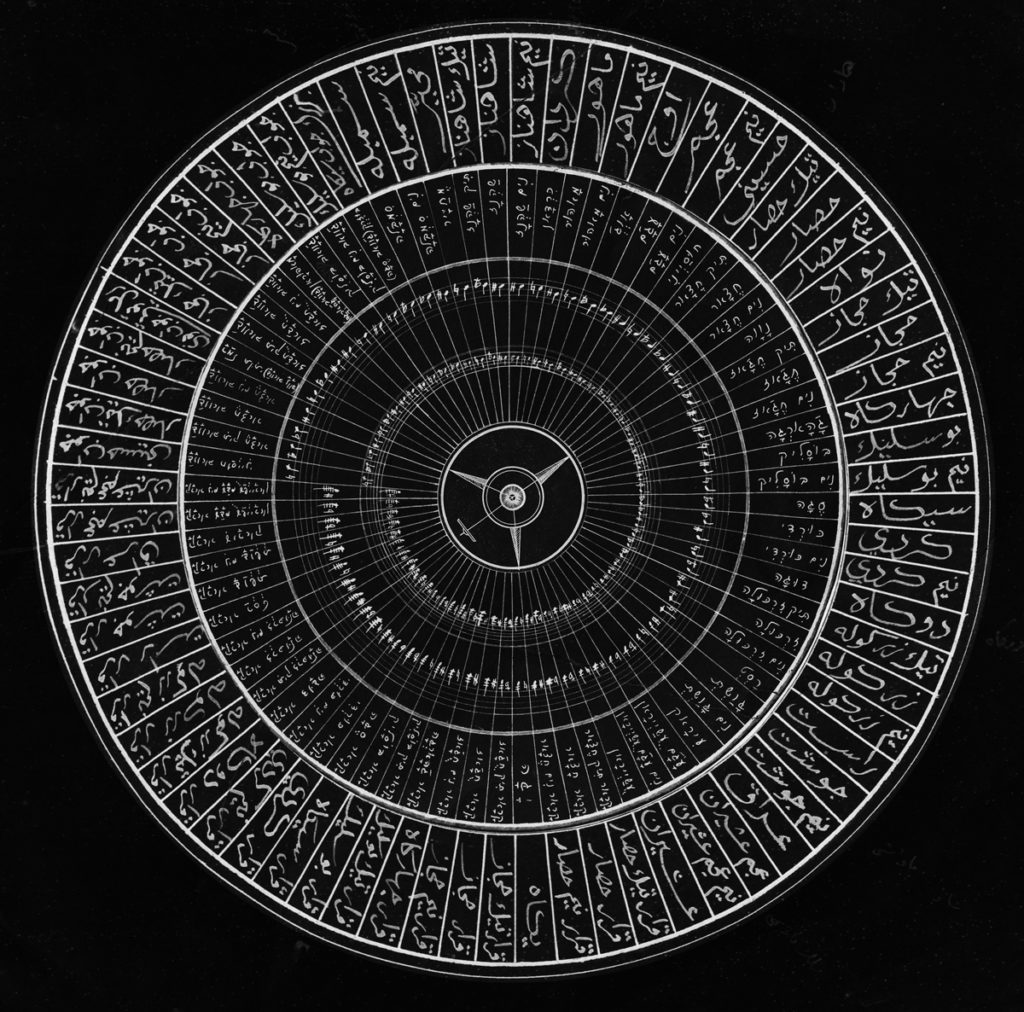

המשלחת העיראקית לקונגרס קהיר (1932), באדיבות הספרייה הלאומית

אל הרגע הזה מבקשים האמנים דור זליכה לוי ואביעד סינמנס לחזור, ולהחזיר אותנו, בתערוכה “מקאמאת“. זהו רגע מיתי ומכונן, רגע של תפארת תרבותית, ולא פחות מכך של עושר חברתי. זהו רגע של שפע של זהויות, שבו היהודיוּת איננה סותרת את הערביוּת, והמזרחיות ממילא מכילה בתוכה גם את המערביות.

בהלחימם את מעגל המקאמים הערבי לזה העברי ולתווים על החַמְשה, זליכה לוי וסינמנס מלחימים מחדש את הזהות ההיא – את האפשרות לזהות שמכילה יהודיות, ערביות ומערביות. בעיבודים האלקטרוניים שהם עושים לכלים האתניים כפי שהם נשמעים בהקלטות מקונגרס קהיר – הקלטות התיפוף של אברהם סאלח שמחה על הרִיק ואלה של נגינת הקאנון של יוסף זערור – הרי שהם מעניקים להם צליל עכשווי, רלוונטי, שמותח קו ישר בין העבר לכאן ולעכשיו, ובוודאי כשעל נגינת הקאנון של יוסף זערור עולה נגינת הקאנון של דוד זערור, הנין שלו. כביכול עברה הנגינה בקאנון במשפחה מדור לדור, אולי אפילו אותו קאנון עצמו. כביכול נמתח קו ישיר בין צלילי הקאנון של הסבא רבא לצלילי הקאנון של הנין. כביכול לקחו זליכה לוי וסינמנס את סרט ההיסטוריה, גזרו אותו אי שם ב-1932, והדביקו אותו ישירות אל הסרט הממשיך מ-2017 ואילך, ללא קטיעה באמצע. כביכול לא חלפו מאז 85 שנים של הגירה, מחיקה, ניכור, אובדן, התעלמות והתכחשות של זהות ושל קהל ושל מנגינה ושל קהילה. של קהילה אחרת.

אבל רק כביכול. שכן באמצעות עיוותים של הצליל, “בריחות” מהמקצבים, חוסר תואם בין המקאם הכתוב בעברית לזה הכתוב ערבית, אי–דיוקים בין המקאם הנבחר על גלגל המקאמים לבין הצליל הנשמע, הגברת הביטים של הרִיק באמצעים אלקטרוניים, או סימפול אלקטרוני של נגינת הקאנון של יוסף זערור שמייצר אווירה של מתח ודריכות – הרי שזליכה לוי וסינמנס מפריעים את התמונה ההרמונית שיכלה להיווצר. הם תופסים את הרגע הזה בהיסטוריה, הרגע ההוא של יצירה משותפת, ערבית–יהודית, מפנים אליו את מבטם, ובוחנים את נקודת המבט העכשווית שלהם על אותו רגע היסטורי, את המבוכה ואת הבלבול שלהם מולו.

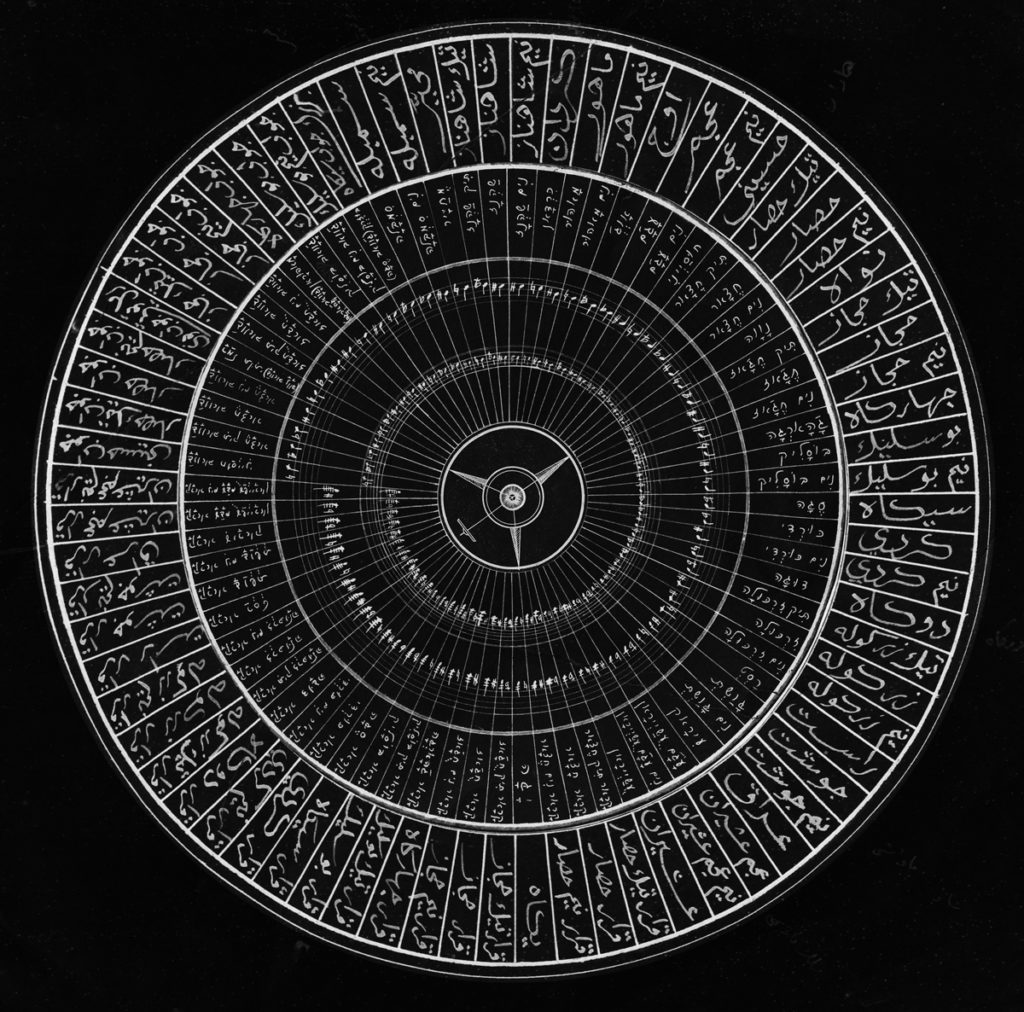

הצופים מתבוננים בגלגל המקאמים, אשר כשלעצמו נראה כמו גלגל מזלות, מתרשמים מיופיו, מהסימטריה והאסתטיקה שלו, ממה שנראה ככתב יד (ייתכן של עזרא אהרון), ומהדיוק. אבל עומדים מול גם כאובדי עצות. למרביתנו אין מושג מה המשמעות של גלגל זה, אולי אפילו מה המשמעות של “מקאם“, או כיצד לזהות מקאם זה או אחר, אולי אפילו איננו יודעים קרוא וכתוב בערבית.

פרט מתוך מקמאת(2017) באדיבות הספריה הלאומית

זליכה לוי וסינמנס עוצרים את הרגע הזה ואוצרים אותו כמעין רגע של שיא, של יצירה מוזיקלית משותפת, של חיים משותפים, של אפשרות אחרת. אבל הם מחזירים אותנו אליו לא כמעשה נוסטלגי גרידא, של התרפקות על עבר מדומיין (לפחות בחלקו), אלא כמעין חזרה אובססיבית של מוכי טראומה, החוזרים שוב ושוב אל הרגע ההוא, שלפני שהכול השתנה. הם כולאים את הרגע הזה בעבודותיהם, אבל לא יותר מכפי שהרגע הזה כלוא ממילא בליבותיהם של אלפי אנשים כבר עשרות שנים. שכן היה זה רגע. גם אם חיו אותו אנשים לכל אורך שנות חייהם, מבחינה היסטורית הרי שמדובר ברגע. ואחרי רגע השיא, כמאמר הקלישאה, חיכה המדרון. אם שנות ה-20 היו בעיני יהודי עיראק “תור הזהב“, הרי שמן המחצית השנייה של שנות ה-30 כבר החלה האווירה להשתנות.

עבור יהודים וערבים כאחד (כמו גם עבור מיעוטים אחרים שחיו בארצות ערב), בשנות ה-20 הרעיון הלאומי – הן הערבי והן הציוני – עוד היה בחיתוליו, מבחינה זו שהתנועות עוד לא הגיעו לכדי התנגשות חזיתית. הזהות הלאומית המקומית – עיראקית, מצרית או אחרת – יכלה עדיין להכיל גם יהודים ובני מיעוטים אחרים, וניתן היה עדיין לדמיין קהילה מרובת מוצאים, מרובת עדות ודתות, שהמשותף לכולם בה הוא השתייכותם לארץ שבה נולדו ובה חיו מדורי דורות. זהו הרגע, כמעט הרגע האחרון, שבו ניתן היה עדיין לדמיין עתיד אחר.

מרבית יהודי עיראק ימשיכו לחיות בה עד למחצית המאה ה-20, ירכשו השכלה, יסחרו וישגשגו כלכלית, יחזיקו במשרות רמות פה ושם ויזכו לאהדת ההמונים כיוצרים. אבל מאמצע שנות ה-30 תלך האווירה ותעכיר. את המלך פייסל יחליף ב-1933 בנו, ר‘אזי, שינקוט גישה נוקשה יותר מאביו, ועל רעיון הלאומיות העיראקית יגבר מעתה רעיון הלאומיות הפאן–ערבית אותה ביקשו להוביל אינטלקטואלים עיראקיים – ולשם לא יכולים יהודים להיכנס. הסכסוך ההולך וגובר סביב שאלת ארץ ישראל/פלסטין, כמו גם התערבותה של התנועה הציונית בעיראק, תרמו רבות להידרדרות היחסים בין היהודים לסביבתם.

אבל אז, באותו רגע של קונגרס מוזיקלי ב-1932, השנה בה זכתה עיראק לעצמאות, איש מחברי המשלחת העיראקית לא יכול היה לדמיין שתוך זמן קצר התעמולה הנאצית תשפיע על הלכי הרוח בציבוריות העיראקית, וכי תוך פחות מעשור, בחג שבועות שחל בחודש יוני 1941, תגיע זו לשיאה באותם אירועים שהתפרסמו בשם “פרהוד” (الفرهود), ושבהם נרצחו לפחות 179 יהודים, מרביתם בבגדאד ובבצרה. איש מבין חברי המשלחת העיראקית לא חלם שבתוך שנים ספורות ייאלצו מרביתם לעזוב את מולדתם, זו שאותה נסעו לייצג, לעולמים. סביר להניח שאף עזרא אהרון, ראש המשלחת, שהתיישב בירושלים כבר ב-1934, לא שיער בנפשו שלא יוכל עוד לשוב לעיראק, מולדתו, או שעם עלייתו לשלטון ב-1979 יורה סדאם חוסיין למחוק את הקרדיט של כל המוזיקאים והיוצרים היהודים מיצירותיהם שבארכיון הרדיו העיראקי.

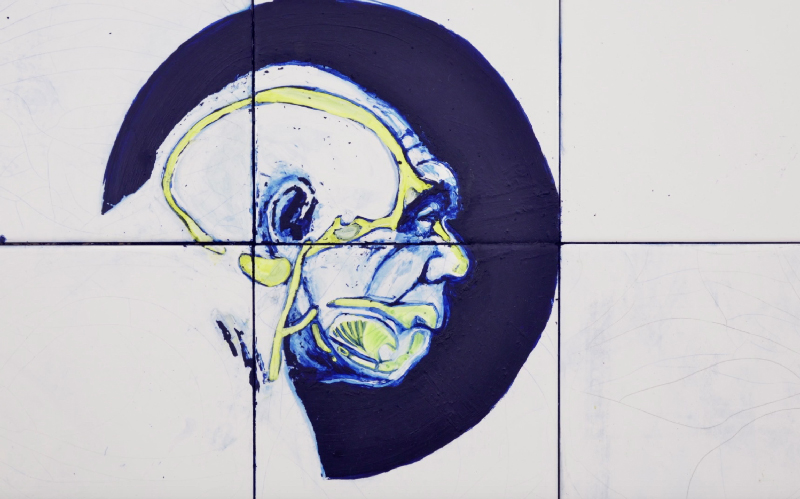

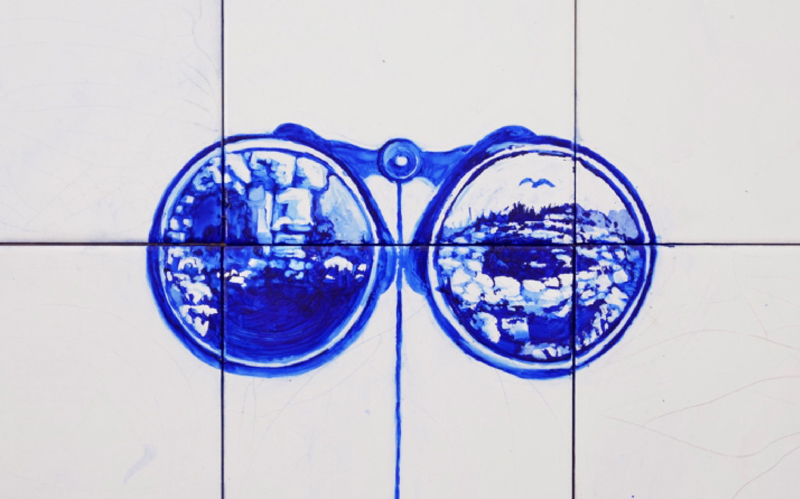

זליכה לוי וסינמנס תופסים את הרגע הזה בהיסטוריה שבו ניתן היה עדיין לדמיין עתיד אחר, שונה מזה שהגיע. ובהביטם אליו – כביכול במבט תמים, תוהה ונבוך – הם מערערים על הרעיון הלאומי כפי שהתפתח להיות, או לפחות על הנרטיב שהוא מייצר. באמצעות תמונת הנוף שהם מייצרים, האמנים מעלים שורה של תהיות מתריסות, “חצופות” במונחים לאומיים, כגון: של מי הנוף הזה? למי הוא שייך? איזו מבין שתי המולדות היא המולדת שלי? מי או מה קובעים לאדם איפה תהיה מולדתו? ויתרה מכך: מי האויב שלי? ומי קבע שהאויב שלי הוא בהכרח האויב שלי?

פרט מתוך מקמאת(2017) באדיבות הספריה הלאומית

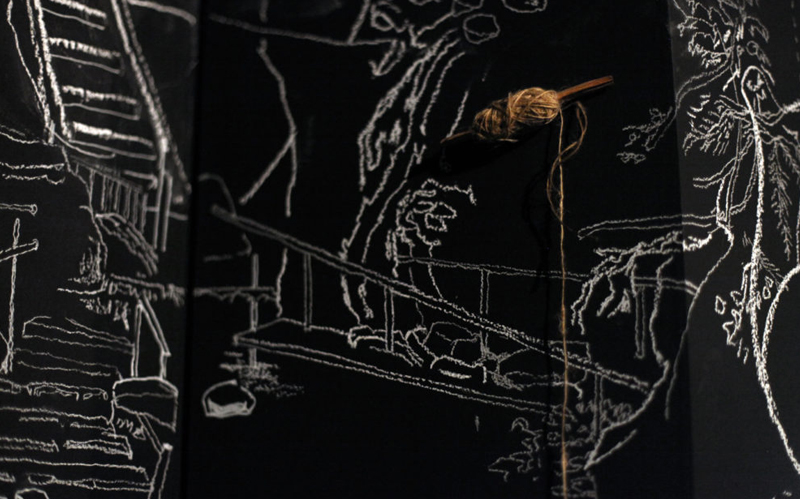

זו אינה הפעם הראשונה שבה זליכה לוי וסינמנס מבקשים להפריע את “הסדר הטוב” הלאומי, לחשוף את הפריצות בנרטיב שלו, לקשקש על התמונה שהוא מבקש לצייר. בעבודהNoon הם מציגים קטע משידורי הטלוויזיה העיראקית, שבו נראה נגן הקאנון העיוור של הזמר נאזם אלר‘זאלי (ناظم الغزالي, 1963-1921) בקטע סולו. הסרט תקוע. חוזר על עצמו. שוב ושוב. נגינתו של הקאנונג‘י הופכת בעזרתו של סינמנס לאזעקת צבע אדום. האזעקה מופרעת על ידי הנגינה, הנגינה על ידי אזעקה, הסרט כולו משובש. כביכול ביקשו להפריע את שידורי הטלוויזיה הממלכתית, הלאומית. “סליחה, תקלה“, אומרים זליכה לוי וסינמנס. אבל לא אצלנו, האמנים או הצופים – אלא אצלכם, מכתיבי המדיניות.

נון (2016), דור זליכה לוי ואביעד סינמנס, מיצב אודיו-ויזואלי

זליכה לוי וסינמנס מתגעגעים בתערוכה שלהם למקום שאיננו עוד, לזמן שלא קיים, וייתכן שגם לא התקיים, אלא לרגע. אבל זהו לא רק הגעגוע שלהם. בשנים האחרונות ניתן למצוא את הגעגוע ליהודים לתקופה בה היוו חלק מהחברה העיראקית גם בשדה התרבות בעיראק: החל מהסרט הדוקומנטרי “שכח מבגדאד: יהודים וערבים – הקשר העיראקי” (2002) של הבמאי העיראקי–שוויצרי סמיר ג‘מאל אלדין (Samir Jamal Aldin, נ‘ 1955), עבור בסדרת הטלוויזיה “סלימה באשא” (2012) על חייה של הזמרת היהודי הסלימה מוראד (سليمة باشا مراد, 1974-1912), דרך תרגום ספרו של אלמוג בהר “צ‘חלה וחזקאל” לערבית והפצתו בעיראק (2016), עד לסרט הדוקומנטרי “על גדות החידקל” של מרשה אמרמן ומאג‘ד שוכּר (Shokor, Emerman; 2015) על אודות המוזיקאים היהודים בעיראק, ועוד. בכך, הופך הגעגוע של זליכה לוי וסינמנס לפעולה. פעולת געגוע אותה הם חולקים עם מי שאסורים לנו במגע.

המילה “מקום” בעברית משמשת בהוראתה הפיזית, אבל גם כאחד משמות האל. “ברוך המקום ברוך הוא“, נאמר בהגדה של פסח. למילה “מקאם” לעומת זאת יש שפע של משמעויות בערבית: מקום, מעמד, סולם מוזיקלי, מקום עלייה לרגל, קבר קדוש ועוד. לצורת הנקבה, “מקאמה“, יש גם משמעות של מקאמה כז‘אנר ספרותי. אבל היות שצורת הריבוי של שתי המילים (גם בצורת הזכר וגם בצורת הנקבה) היא “מקאמאת“, הרי שבתרגום ישיר של שם התערוכה לעברית, סתם כ“מקומות“, מצטמצמת המשמעות של המילה לזו הפיזית בלבד, המשמעות של מקום, והיא מאבדת הן מהממד המוזיקלי שלה הקיים בערבית, הן מהממד הרוחני ואף האלוהי שקיים בעברית. ואולי בעצם זוהי אותה משמעות אחת, שאבדה.